内容简介:Abusing legacy functionality built into the Microsoft Office suite is aMalware campaigns, such as the ZLoader campaign (described in great detail by InQuest LabsWhile there is clearly already a spotlight on the subject of Excel 4.0 Macros, I believe that o

Abusing legacy functionality built into the Microsoft Office suite is a tale as old as time . One functionality that is popular with red teamers and maldoc authors is using Excel 4.0 Macros to embed standard malicious behavior in Excel files and then execute phishing campaigns with these documents. These macros, which are fully documented online , can make web requests, execute shell commands, access win32 APIs, and have many other capabilities which are desirable to malware authors. As an added bonus, the Excel format embeds macros within Macro sheets which can be more challenging to examine statically than VBA macros which are easier to extract. As a result, many malicious macro documents have a much lower than expected rate of detection in the AV world.

Malware campaigns, such as the ZLoader campaign (described in great detail by InQuest Labs here , here , and here ) are actively abusing this functionality to perform mass phishing attacks. The campaign is so prolific that I’ve actually received one of these maldocs in one of my personal email accounts. Because of its effectiveness and low detection rate, this technique is also popular in the penetration testing community. Outflank described how to embed shellcode in Excel 4.0 Macros in 2018 , and tooling has been published to abuse this functionality via Excel’s ExecuteExcel4Macro VBA API .

While there is clearly already a spotlight on the subject of Excel 4.0 Macros, I believe that only the surface of this attack vector has been scratched. There’s no doubt that defenders are building better signal on malicious macros (one of the tools which originally had 0 detections on VirusTotal is now up to 15 at the time of writing this post), but there is also evidence that some of this signal can be brittle and unreliable.

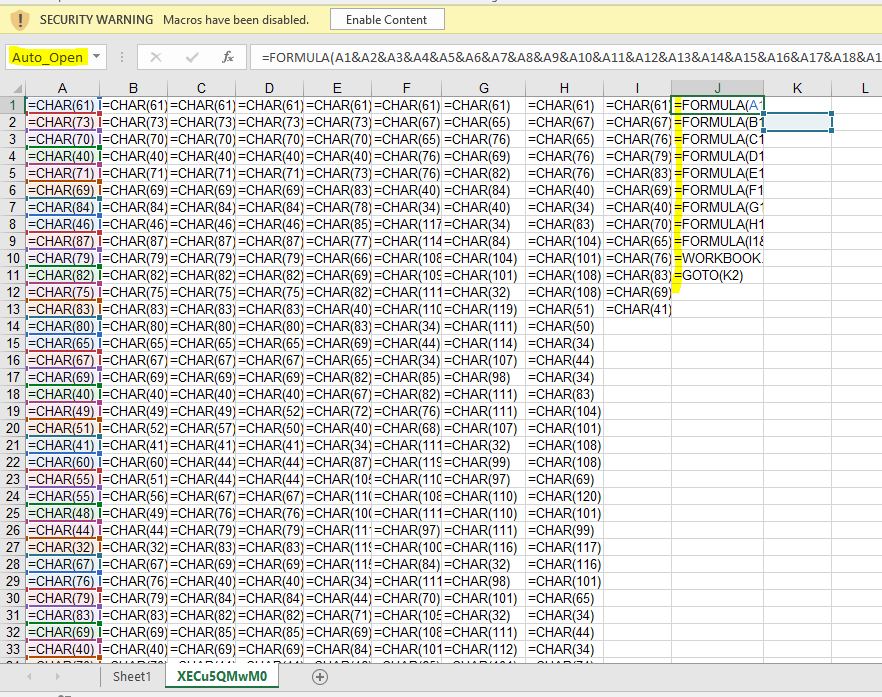

For example, the ZLoader campaign obfuscates its macros using a series of cells that build each command from CHAR expressions. Ex: =CHAR(61) evaluates to the = character.

There’s plenty to build a signature on in this sheet:

- The repeated usage of the =CHAR(#) cells to define formula content one character at a time.

- The use of the Auto_Open label which triggers automatic execution of the macro sheet once the “Enable Content” button is pressed.

- ZLoader marks their macro sheets as hidden which has a detectable static signature

- The use of numerous Formula expressions to dynamically generate additional expressions at runtime.

A lot of this would appear to be good enough signal to just block outright – Windows Defender, for example, considers just about any usage of =CHAR(#) to be malicious. Making an empty macro sheet that contains one cell with =CHAR(42) and another with =HALT() will immediately flag the document as malicious:

This is probably a bit overkill, but apparently the number of legitimate users that do this is small enough that Windows can roll out a patch to all machines marking it malicious. A more reasonable signature, which seems resistant to false positives, is @DissectMalware’s macro_sheet_obfuscated_char YARA rule:

rule macro_sheet_obfuscated_char

{

meta:

description = "Finding hidden/very-hidden macros with many CHAR functions"

Author = "DissectMalware"

Sample = "0e9ec7a974b87f4c16c842e648dd212f80349eecb4e636087770bc1748206c3b (Zloader)"

strings:

$ole_marker = {D0 CF 11 E0 A1 B1 1A E1}

$macro_sheet_h1 = {85 00 ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? 01 01}

$macro_sheet_h2 = {85 00 ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? 02 01}

$char_func = {06 ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? 1E 3D 00 41 6F 00}

condition:

$ole_marker at 0 and 1 of ($macro_sheet_h*) and #char_func > 10

}

This rule looks for three things:

- The standard magic header for Office documents D0CF11E0A1B11AE1 at the start of the file.

- A macro sheet (defined in a BoundSheet8 BIFF Record ) with a hidden state set to Hidden or VeryHidden .

- The presence of at least 10 Formula BIFF Records which have an Rgce field containing two Ptg structures – a PtgInt representing the value 0x3D (which maps to the = character) and a PtgFunc with an Ftab value of 0x6F (the matching tab value for the CHAR function).

Unless you are fairly acquainted with the Excel 2003 Binary format (also known as BIFF8) , the third search condition is likely to read as a series of random letters jammed together rather than anything coherent. To better understand what exactly is being discussed, let’s take a quick detour into the BIFF8 file format.

The Excel 97-2003 Binary File Format (BIFF8)

Before office documents were saved in the Open Office XML (OOXML) format, they were saved in a much more succinct binary format focused on describing the maximum amount of information with the minimum number of bytes. Legacy office documents are stored in a Compound Binary File Format (CBF) while their actual application specific data (such as Word document content or Excel workbook information) is stored within binary streams embedded in the CBF header.

Excel’s workbook stream is a direct series of Binary Interchange File Format (BIFF) records. The records are fairly simple – there are 2 bytes for describing the record type, 2 bytes for describing the remaining length of the record, and then the relevant record bytes. An Excel workbook is just a series of BIFF records beginning with a BOF record and eventually ending with a final EOF record . Microsoft’s Open Specifications project has helpfully documented every one of these records online . For example, if we are parsing a stream and read a record beginning with the byte sequence 85 00 0E 00 , we are reading a BoundSheet8 record that is 14 bytes long.

From Microsoft’s documentation we can see that BoundSheet8 records contain a 4 byte offset pointing to the relevant BOF record, 2 bits used for describing the visible state of the sheet, a single byte used for describing the sheet type, and a variable number of bytes used for the name of the sheet.

The above hex dump represents a BoundSheet8 record for a Macro sheet that has been “Very Hidden” – essentially made inaccessible from within Excel’s UI. This record would match the YARA sig byte regex of $macro_sheet_h2 = {85 00 ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? 02 01} . The signature begins with the matching BIFF record id for BoundSheet8 ( 85 00 ), then ignores the size (2 bytes) and the lbPlyPos record (4 bytes). It then matches the hsState field ( 02 ) followed by the byte indicating that the sheet is a macro sheet ( 01 ). This is a reasonable match for sheets that follow the BIFF8 specification.

Fiddling with BIFF Records

However, there are a few tricks to essentially dodge this signature component by abusing flexibility in the specification. For example, the hsState field is only supposed to be represented by 2 bits – the remaining 6 bits of that byte are reserved. Theoretically this means that touching these bits should invalidate a spreadsheet, but this is not what happens in practice. Say we replaced the value 02 (b’00000010 in binary) with a different value by flipping some bits (b’10101010) like AA – would Excel also treat that as a hidden sheet? I can’t speak for all versions of Excel, but in my testing with Excel 2010 and 2019, the answer is yes.

Essentially, by following the majority of the specification, but not following the exact way that Excel has traditionally generated these documents creates an entirely new set of Excel binary sheets which bypasses most static signatures. The remainder of this blog post will focus on a few examples of abusing the BIFF8 specification to create alternate, but valid, Excel documents.

Label (Lbl) Records

Lbl records are used for explicitly naming cells in a worksheet for reference by other formulas. In some cases, Lbl records can contain macros or trigger the download and execution of other macros . From a malicious macro author’s perspective, though, the most likely usage of a Lbl record is to define the Auto_Open cell for their workbook. If a workbook has an explicitly defined Auto_Open cell then, once macros are enabled, Excel will immediately begin evaluating the macros defined at that cell and continue evaluating cells below it until a HALT() function is invoked. Understandably, the existence of an Auto_Open Lbl record is considered fairly suspicious, so there are a number of workarounds attackers have taken to hide their usage of this functionality. Let’s see if there are some other evasion techniques hiding in the Lbl record specification:

By default, when an Auto_Open label is defined in a BIFF8 document, it has its fBuiltin flag set to true, and its name field set to the value 01 , indicating that this is an Auto_Open function. The first 17 bytes of this record (21 if you include the 4 byte header) can likely be used as a signature to identify usage. This does assume a lack of meddling with the reserved bytes which default to 00 , but signatures could probably replace these with wildcard bytes and not pick up too many false positives. Given that normal labels are never going to have a single byte value of 01 , there is a very small chance of triggering false positives with this as well.

If a user attempts to save any variation on the Auto_Open label (like alternative capitalization AuTo_OpEn ), Excel will automatically convert it back to the shortened fBuiltin version shown above. However, when Excel opens an OOXML formatted workbook there is no equivalent shorthand record for Auto_Open , it is simply stored as a string. So what happens if we explicitly create a Lbl record, leave fBuiltin as false, and give it a name of Auto_Open ?

If a Lbl record is generated with these properties and inserted into an Excel document, Excel will still treat the referenced cell as an Auto_Open cell and trigger it. So we can create a label that triggers Auto_Open behavior but doesn’t look like the default record. This is a good start, but once a technique like this became well known it would also be vulnerable to a quick signature. As is, there are already plenty of AV solutions that will explicitly look for the Auto_Open string since attackers have been abusing this in OOXML documents in the wild.

Excel is surprisingly flexible when it comes to considering a text field matching the Auto_Open label – apparently the application only checks if the label starts with the string Auto_Open . This results in maldocs with labels like Auto_Open21 . In fact, if you use Excel to save a label with name like Auto_Open222 , it will actually save the record using a combination of the fBuiltin flag, and then append the extra characters, as can be seen below.

Appending characters is great, but can we inject additional characters into the Auto_Open string in a way that Excel will still read it? A common trick in bypassing input validation is to try injecting null bytes to see if it results in the string being terminated early. Occasionally null bytes are also good for changing the length of a string without affecting its value.

Excel will actually give us the best of both worlds, from an attacker perspective, when injecting null bytes. The Auto_Open functionality will remain intact and still trigger for the cell we specify, but the Name Manager will not properly display any part of the name after the first null byte. Additionally, our Lbl record’s name data will not be easily match-able with a predictable regex.

The rabbit hole actually can go deeper than just null byte injection, however – the Name field in Lbl records is represented by a XLUnicodeStringNoCch record. This record allows us to specify strings using either (essentially) ASCII or UTF16 depending on whether we set the fHighByte flag. Besides further breaking any signatures relying on a contiguous Auto_Open string, the usage of UTF16 opens a whole new world of string abuse to attackers.

Unicode is traditionally a parsing nightmare in the security space due to inconsistent handling of edge cases across implementations. Excel is no exception to this, and it appears that when an unexpected character is encountered, the label parsing code will simply ignore it. From testing it appears that any “invalid” unicode character found will be skipped entirely. There are likely exceptions to the rule, but it appears that any entry that claims to be an invalid combination on fileformat.info can be injected into XLUnicodeStringNoCch records without impacting parsing. For example, if we build a string like "\ufefeA\uffffu\ufefft\ufffeo\uffef_\ufff0O\ufff1p\ufff6e\ufefdn\udddd" , this will still trigger the Excel Auto_Open functionality.

This could be combined with null byte injection to hide the manipulation from the Name Manager UI entirely, or the Lbl record’s fHidden bit could be set to stop it from appearing in the Name Manager entirely. The ability to inject an arbitrary amount garbage in between letters in the Lbl name significantly increases the difficulty of building a reliable signature for this technique.

The Rgce and Ptg Structures

Let’s revisit the YARA rule from earlier, specifically the part for detecting usages of =CHAR(#) :

$char_func = {06 ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? 1E 3D 00 41 6F 00}

This signature is keying on the beginning of a Formula record, and then the CellParsedFormula structure towards the end. CellParsedFormula structures contain three things:

- cce – The size of the following rgce structure

- rgce – The actual structure containing what we’d consider to contain the formula

- rgcb – A secondary structure containing supporting information that might be referenced in rgce

So what on earth is an Rgce structure? Why it’s a set of Ptg structures of course! Ptg structures, short for “Parse Thing” , are the base component of Formulas. While one might expect to find a string representation of a formula like =CHAR(61) , this wouldn’t mesh with BIFF8’s hyper-focus on reducing file size. Each formula is represented as a series of Ptg expressions which describes a small piece of what a user would consider to be a formula. For example, =CHAR(61) is in fact two components – a reference to the internal CHAR function, and the number 61 . Each of these representations has a corresponding Ptg structure.

The CHAR function is represented by a PtgFunc , a Ptg record which contains a reference to a predefined list of functions in Excel known as the Ftab .

The number 61 is represented by a PtgInt structure which is just the standard Ptg header and an integer with the value of 61:

As a result, we end up with the binary signature of 1E 3D 00 41 6F 00 ( 41 is the Ptg number for PtgFunc ). One thing that might stand out here, however, is the fact that the ordering of this data seems backwards – the PtgInt (61) data is stored before the PtgFunc ( CHAR ) data.

This is because Ptg expressions are described using Reverse Polish Notation (RPN). RPN allows for quick parsing of a series of operators and operands without needing to worry about parentheses, items are processed in the order they are read. For example: 3 4 − 5 + represents taking the value 3 and 4, then applying the subtraction function to those values to get -1. The value 5 is taken and the addition function is applied to -1 and 5, resulting in 4. This mentality is useful for stack-based programming languages, and it is used here to simulate what is essentially a stack of Ptg expressions. In our example here, the operand PtgInt (61) is popped off the stack, then the PtgFunc ( CHAR ) is applied to it.

The reason this is relevant is because the RPN stack-based format of Ptg structures allows us to easily create some very obfuscated expressions without needing to worry about their binary representation. For example, Microsoft Defender blocks all =CHAR(# ) expressions – but what if we write a formula like =CHAR(ROUND(61.0,0)) . This function is essentially the same, but ends up being represented very differently at the byte level:

The rgce listed here is now PtgNum (61.0), PtgInt (0), PtgFunc ( ROUND ), PtgFunc ( CHAR ). As an added “bonus”, PtgNum represents its data as a double, so the value of 61 is represented as 00 00 00 00 00 80 4E 40 . Embedding a function has also completely changed the order of our Ptg structures such that the bytes of PtgFunc ( CHAR ) and PtgNum (61.0) are no longer adjacent. The original signature of 1E 3D 00 41 6F 00 is no longer tracking this Formula.

In short, the rgce block is ideally designed from a malware author’s perspective. There are numerous ways to represent the exact same functionality that look completely different from a static analysis perspective. The byte layout of the rgce block is also highly sensitive to change, turning a single value into a function invocation can rearrange the order of all other Ptg bytes within the expression.

Introducing Macrome

Much of the work necessary for testing some of these methods involved manually writing XLS files rather than using Excel. While there are plenty of tools for reading the BIFF8 XLS format, good tooling for manually creating and modifying XLS files doesn’t appear to be as common. As a result, I’ve created a tool for building and deobfuscating BIFF8 XLS Macro documents . This tool, Macrome , uses a modified version of the b2xtranslator library used by BiffView .

Macrome implements many of the obfuscations described in this blog post to help penetration testers more easily create documents for phishing campaigns. The modified b2xtranslator library can be used for research and experimentation with alternate obfuscation methods. Macrome also provides functionality that can be used to reverse many of these obfuscations in support of malware analysts and defenders. The tool was originally going to include functionality to process macros to help bypass obfuscated formulas, but @DissectMalware has already created a fantastic tool called XLMMacroDeobfuscator which goes above and beyond anything I was planning on dropping. It’s really a great piece of tech that I’d recommend anyone who has to analyze these kinds of documents.

I’ll be posting in the future about how to further expand Macrome and implement your own obfuscation and deobfuscation methods. In the meantime, please give the tool a try at https://github.com/michaelweber/Macrome . If you have any suggestions or feature requests please let me know here or open an issue!

以上就是本文的全部内容,希望对大家的学习有所帮助,也希望大家多多支持 码农网

猜你喜欢:本站部分资源来源于网络,本站转载出于传递更多信息之目的,版权归原作者或者来源机构所有,如转载稿涉及版权问题,请联系我们。

啊哈C语言!逻辑的挑战(修订版)

啊哈磊 / 电子工业出版社 / 2017-1 / 49

《啊哈C语言!逻辑的挑战(修订版)》是一本非常有趣的编程启蒙书,《啊哈C语言!逻辑的挑战(修订版)》从中小学生的角度来讲述,没有生涩的内容,取而代之的是生动活泼的漫画和风趣幽默的文字。配合超萌的编程软件,《啊哈C语言!逻辑的挑战(修订版)》从开始学习与计算机对话到自己独立制作一个游戏,由浅入深地讲述编程的思维。同时,与计算机展开的逻辑较量一定会让你觉得很有意思。你可以在茶余饭后阅读《啊哈C语言!逻......一起来看看 《啊哈C语言!逻辑的挑战(修订版)》 这本书的介绍吧!